Exclusive interview: Airspeed

Many people don’t know that Airspeed skateparks designed the only currently-standing skatepark in Seattle, the new Ballard Bowl. Airspeed’s co-owners Stephanie Mohler and Geth Noble, knowingly walked into a politically charged environment and executed on a design that created some controversy of it’s own.

Many people don’t know that Airspeed skateparks designed the only currently-standing skatepark in Seattle, the new Ballard Bowl. Airspeed’s co-owners Stephanie Mohler and Geth Noble, knowingly walked into a politically charged environment and executed on a design that created some controversy of it’s own.

Seattle’s skaters had just fought and lost a hard battle to save the original Ballard Bowl, a monument of sorts, that was built and paid for by skaters and the community. The job of designing a replacement for such a beloved and revered bowl would not be an easy task. But when it came to to build the bowl, Grindline principle and chief Mark Hubbard (a major player in donating the time and resources for the original Ballard Bowl) wanted to remove the defining feature of the design. Drama ensued.

The end product has been a huge success, and the new Ballard Bowl continues to be a prime example of how integrating a major skate feature into a high-profile public space can be a win for everybody. In this interview, Stephanie took some time to sit down and reflect on that project as well as impart some wisdom from the observation deck aboard the USS Airspeed.

Enjoy.

State your name for the record

Stephanie Mohler, Co-Owner, Airspeed Skateparks

How many skateparks have you guys/gals built to date?

3.1 billion like MC Donalds no really like 30

Obviously you prefer to work on projects that you can design and build for professional and creative control, but how do you think skaters benefit from design/build?

Skaters benefit from using the design-build method by knowing that the design established through the public design process will be realized to a great extent in the field. Design-build provides continuity of the public design process, rather than changing horses mid-stream from designer to builder. If a design is arrived at through the public process and it is done design-build then the skaters have some insurance that that design will come to fruition.

We’ve heard that the city benefits from having a separate designer and builder because it provides a built in set of checks and balances for construction costs and keeping on schedule. Are there ways to give them the assurances they want and keep it a design/build project?

For cost control, I suggest using the checks and balances we have used on almost every project: open book accounting. It is a transparent way for Cities to keep track of spending. As for on-time completion, cities should contact design-build firms’ references and get hard facts from City Project Managers on how the design-build firm performed. It is important for cities to research prior projects even if the design-build firm has not listed them as references–a little extra investigation may reveal things that have gone under the radar.

What’s the best way for skatepark advocates to assure that their city will only use qualified companies to build their skateparks? There seem to be a lot of wanna-be companies out they’re trying to build parks these days.

This is a very subjective question. Let’s face it, many people like what is advertised in the mass media and what is repeated a million times true or not. It’s wrong to think that a company that has done 100 jobs is necessarily more expert or experienced than a company focusing on high quality and creativity. As members of consumer culture, we are brain washed or bullied into supporting companies with strong marketing and media coverage. Skatepark designing and building falls prey to marketing, personal agendas, group agendas, company agendas, just as much as any other realm. Everyone started as wanna-be companies. There are lots of riders with dreams of designing and building, but it is a difficult business, which I think a lot of people don’t realize.

You guys run public design meetings and like to get the local skaters involved in their new park. Let’s say I am a street skater and I want the new park to have something for me, What is your recommendation for preparing for the design meeting so I can get what I want? What should I bring?

Bring your ideas, someone to verbalize them and your friends to back you up. Draw out design idea(s), which can be hand transferred to the designers if one is on the shy side or on the non-verbal side. Represent yourself. I know it can be intimidating and feel like nobody will listen or cares and sometimes it’s true. So, it is really important that the riders support design-builders that will listen to the local skaters and incorporate their ideas.

Every skatepark meeting in Seattle seems to have a few neighbors in it that are worried about noise, graffiti, and the typical misperceptions of what a skatepark is. How are you guys currently addressing these recurring design issues in your current designs? Are there some things that advocates can ask for up front in the design that will help cut these arguments off preemptively?

The most important thing is to really listen to other people’s concerns. They are usually sincere even if they seem crazy or uneducated to riders themselves. Show them you care and give them respect, the same respect you would like to get for yourself and your design ideas and concerns. Most people just need to be heard. Once they are heard and understood, most people will work for the benefit of the skate facility. Win them over and bring them into the skate world through kindness and understanding. Be like Gahndi ( try!).

So, skate facility advocates can ask up front what the neighbors concerns are and then in the design process work creatively with the designer to find solutions. Educate the neighbors on how certain design features alleviate their concerns. For example, Airspeed is designing a skate park in Gabriel Park, Portland, OR. There is a neighbor who is hypersensitive to noise. We have designed the park to direct noise away from her house and are including a row of trees to further attenuate the noise.

At all the design meetings I’ve been to, people seem to ask for features they’ve skated elsewhere. Is this a good thing or should we be encouraging the designer to try new things? What’s the best way to do this?

It’s human nature to want familiar things. People’s own internal limits are on display when asking for features they skated elsewhere to be repeated in the design. It is totally understandable; lots of people resist change and are not comfortable with new ideas and challenges. I think the designer should try to address this part of human nature but also push the limits of what is presently accepted and loved. One doesn’t know they could love something new if one never has the opportunity to experience new terrain. We are now running into this a lot with the rise of skatepark advocacy groups (usually representing an older age group of riders). Before it was mostly kids who thought they could never like tranny riding (but end up loving it along with street) but now there also seems to be a movement of older riders pushing for what they call “classic elements”. It’s understandable with the aging process underway and tons of fond memories from days gone past. I believe there is room and a place for everything, the classic features, new ideas, street, it’s all an open book, why limit ourselves and others?

Airspeed parks seem to focus around a single cutting-edge feature that hasn’t appeared in any other park. Is there a philosophy behind this?

This assertion is one I first heard from another company’s lawyer, who has been repeating it ad nauseum like some sort of Fox News skate pundit. In reality, our parks focus on many cutting edge features! For example, Florence has 3–the Tractor Seat, the Hot Wheels Track and the Over-Vert Hot Wheels Track. These features, first seen at Florence have all been replicated elsewhere by our friends and other skate facility designers and builders. Likewise, we have been doing cutting-edge stamped concrete brick, rock, and tile since 2003. See Reedsport, OR, Waldport, OR, and Florence, OR. Recently now, other companies are now getting on board with the stamping and it’s great to see!

Our philosophy is progression and creating new terrain that offers new skating sensations for riders: experience the unknown coupled with riding familiar fun obstacles. It’s one of our major strengths. We also build classic fun facilities like Bethel, Newburyport, Toledo, Johannesburg and Dublin.

Ultimately we design and build what the community wants. For Gabriel Skatepark we initially proposed the “Double Funnel†but the local skatepark advocates wanted a retro 70’s snake run so we are now designing their vision. We have a town out in Kendallville, Indiana that wants to build the “Double Funnel†so it all works out. Some groups want cutting edge stuff, some want street plazas, others want classic replicas, we design and build it all. We have been fortunate to work with communities that support progression. The resulting parks have helped their local economies and put towns on the map like Reedsport, Waldport, and Florence, OR.

What project have you worked on that you think Seattle’s skatepark advocates can learn the most from politically speaking?

Our company home town Florence, OR. It took 15 years of grassroots and political work to get the project designed and on the ground. Gain supporters through positive means and education. I have been noticing recently a negative approach and bullying to try and get what riders want but ultimately it detracts from all of our lives and our scene and is lowering our quality of life. It really is a big corporation mentality and a sick person’s/society approach. People do not like to be bullied and threatened, so do unto others as you would want others to do unto you.

Airspeed has built parks all over the world. What are some of the differences in terms of the process when building a park in another country? Is it more difficult to build a park in the US than in other countries? Give us some worldly perspective!

It is not more difficult to build parks in the USA, just different. Processes vary depending on the country. In places like Ireland and England it is a similar Request for Proposal process called Tenders, they require similar design requirements for building permits and have similar construction requirements. In Ireland they are really big on Safety Plans while building like wearing florescent “vizzie vests†and hard hats. In Mexico the process is working with some of the best concrete masons in the world and in Johannesburg, South Africa it requires the ability to wheelbarrow 10,000 square feet of concrete and speak several languages simultaneously. So, many countries require doing concrete without all the fancy heavy equipment found in the USA that makes back breaking labor a little less brutal. Other people’s concepts of time and efficiency are different and require patience and cultural understanding. People in other countries are thankful and appreciative of the backbreaking effort the design build crew puts into making their park. Getting materials can be more difficult and tricky, having to learn new or different names of products and tools needed to do the job but the cultural exchange is amazing and we have met many incredible people through designing and building abroad.

Seattle currently has a citywide skatepark plan with 27 pre-designated sites for skateparks on it. What do you think would be the best way to assure an even distribution of types of skateable terrain across the whole system? How would you envision it? Should there be beginner parks and advanced parks or is it better to have a mix of stuff at each location? Street vs. transition in dedicated parks?

The skatepark system should have a bit of everything. Some facilities all street, some mixed street and tranny, some trannny, some skate spots and pathways, beginner, multi level parks, etc…. I think the skate facility system should look something like a healthy forest ecosystem: diverse. In a healthy forest there are multiple types of plants, trees, bacteria, fungi, and animals all co-existing, keeping everything in balance and able to survive and thrive.

What’s your opinion on Seattle’s skatedot concept? What issues do you see with exploding the skatepark into single features scattered around town?

I think it’s a great idea. Often we just feel like sessioning one thing, not in a skatepark/facility social setting. I love the idea and want to see it realized.

Let’s move on to what happened with the Ballard Bowl 2…In hindsight is there anything you wished you would’ve done differently?

Yes, started another company under another name and bid on the job ourselves and realized the design.

There was a bit of a controversy over the design change, the removal of Airspeed’s “pierced cradle” feature, which was something they felt strongly about. Do you still think that was a good decision?

We never thought it was a good decision. In our opinion, the riders of Seattle got short-changed by their local company but the local skaters supported the removal and are happy with the present bowl and that’s great!

To say that project was politically charged would be an understatement. Does that kind of “heat” help or hinder a project? In what way?

Depends, each life situation is unique. I was not on the inside and do not know all the internal workings in this case I would say it was a hindrance because now the Ballard Bowl in my opinion, is just a okay bowl where it could have been a masterpiece.

There was more than one design change. There was some vert added all the way around the deep end and the extension was added. What was the thinking that went in to these changes?

The contractor had to do something once they decided they couldn’t build the over vertical stuff. I think they can best answer this question. Over vertical structures are more difficult to build than a bit more vert and tranny extension.

If Ballard would’ve been design/build, what would’ve been different?

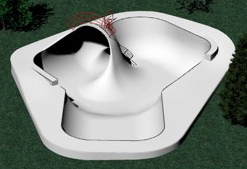

I can’t say how it would have been if another company designed and built Ballard. But if Airspeed had built it you all would have been carving and piercing the Eye Socket, rolling in from the roof, blasting airs off of hips, enjoying the stamped concrete details, and having something different to ride that does not exist yet in Seattle.

By the way…It was amazing that the City of Seattle was going to support an over-vert structure. Big cities tend to be ultra conservative and stifle creativity wherever possible. It was to be a major milestone for large cities and skaters everywhere. For years skaters and design-builders had been pushing for over-vert and creative design freedom. The City was supporting the advance that many of us had been working towards for years.

I see it as a lost opportunity shut down by skaters themselves, shocking but telling.

Thanks for taking the time for this interview, is there anything else you want to add that you think the Seattle skaters need to hear?

Try to remember how lucky and how much we have here in the USA and to be grateful for all that we have. There are tons of riders around the world that have nothing but a few jankety curbs or a hodge-podge mini ramp, they are stoked to have it.

When choosing to effect change opt for routes that continue to build positively along with progression. Take a look at our website and I’d like to see more diverse design-build crews with women and more minorities and design and construction focusing on better environmental practices. Feel free to contact us at Airspeed if you would like to know more about Environmental and Social sustainability designed and constructed into public skate facilities.

Thanks Stephanie!

One Reply to “Exclusive interview: Airspeed”